Worlds of Possibility

The Changemaker Authors Cohort, a partnership with the Unicorn Authors Club, is a new, yearlong intensive coaching program supporting full-time movement activists and social justice practitioners to complete books that create deep, durable narrative change, restructuring the way people feel, think, and respond to the world. This interview series features participants in the inaugural cohort.

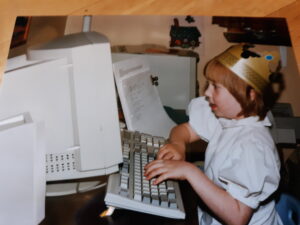

Hans Lindahl is a writer, storyteller, and advocate for intersex communities. I’m Going Through Something, a graphic novel for young adults, is inspired by Hans’ experiences as a young, intersex person.

NI: Tell me a bit about who you are and what you do.

Hans: I’m Hans. I’ve been working in the space of the US intersex movement for almost even 10 years, at least, if you count having started as a teenager. Most recently, I was the former Communications Director for interAct Advocates for Intersex Youth, which is a national law and policy organization. It works within the legal realm to expand choice for intersex people, particularly on the issues of invasive genital surgeries and hormone treatments. Although people often think these medical interventions are pushed on trans youth, they are actually forced upon very young, intersex infants and adolescents, whose bodies, in terms of sex diversity, are just different. Through that experience, I learned a lot about different medical and policy narratives and how issues of bodily autonomy intersect with other issues here in the U.S. and globally. While doing all of that work, I also have been very dedicated to storytelling. I have a YouTube channel where I try to make some of this knowledge accessible, promoting non-medical narratives of understanding sex diversity and intersex movements in the U.S. I also produced storytelling projects with community members talking about their experiences, their visions for a world — one where intersex people are free from medical interventions that they don’t opt into and everyone has choices about genital surgeries. So, coming from that lens and coming from having had the privilege of growing up in intersex community from a very young age, even as a teenager – which is quite rare – I’m much more interested in narrative than law and policy, at least as it concerns my ability to make an impact. This particular graphic novel starts with my own story. I think that’s going to be a great place to start for an author. And I’m really excited the project is picking up a lot of momentum. I received grants to start working on a manuscript and have signed with an agent. So I’m excited.

NI: You mentioned that procedures that are increasingly prohibited for both transgender youth and adults are imposed on intersex people. That’s an interesting contradiction. What does intersex actually mean? Tell me about this culture of medical intervention, if you will, as it relates to intersex people.

Hans: I would say that “intersex” describes a recent movement and also a recent term for identity. And what that refers to, most broadly, is sex diversity–people that are born with unique or unexpected combinations of genitalia (internal/external reproductive organs), hormone expression, hormone balance, things like that. So it’s a very broad umbrella, and intentionally so. There are also narratives, as you mentioned, about medical control, policing who and what fits under that umbrella. Intersex bodies have always posed a unique threat to the sort of colonial binary gender systems on which everything rests and, historically, medicine has always been an enforcement tool. The political climate is such that we have this medical model of intersex in which many specialists — scientists, doctors, people who generally are connected to institutions who benefit from these sorts of interventions on young children — are pushing for control of this medical mode, one that links intersex identities to these specific medical conditions.

NI: So there is a medical intervention approach to interacting with intersex folks that says, “This is a problem that needs to be fixed.” What are more productive or affirming ways of approaching intersex issues?

Hans: We see this tension in medicine, volleying for control over what intersex means, as an emerging term, and wanting that to be a very tight and constricted and controlled definition. As an intersex activist, I would advocate for bodily autonomy movement and for a much broader umbrella that transcends specific medical symptoms or diagnoses. Those are two views that are inherently in conflict.

NI: What are the deeper narratives that inform the way that people who are not intersex perceive intersex people? What deeper issues are at stake here? What has created an environment where these harmful approaches to to intersex identities and the lived experiences of intersex folks exist?

Hans: Fundamentally, it’s always colonialism and white supremacy – those forces using the institution of medicine as an enforcement tool to “deal with bodily diversity.” Disability justice talks about how someone’s not inherently wrong or flawed. While medicine is a means of accessing things that can alleviate symptoms, its practices do not inherently center bodily autonomy. It’s more about enforcement of social norms; that runs contrary to how nature really works. While it can sometimes be tokenizing to invoke intersex people for the sake of this argument, intersex people have such deep wisdom to offer. Having had to contend with these medical models and state enforcement of gender ideas on our bodies, intersex people, I think, are also very much canaries in coal mines. We see things like selective abortion based on intersex chromosomes and other truly scary eugenicist things. Of course, you can have other medical symptoms that require management, but, really, I would view that as no different from any other person’s health issues. You might have certain health issues across the lifespan, but otherwise, you lead a mostly typical life. Using tools like science to pinpoint these human differences is so fundamentally dangerous. I see these narratives about people looking for transgender brain differences. And it’s scary. I mean, I think intersex people challenge mainstream LGBT narratives. The “Born This Way” narrative, for example, is so lacking, right? You shouldn’t have to prove that you have a bodily marker, or that you just are born congenitally a certain way, in order for something to be accepted or even tolerated. It just is. Science and medicine can be oppressive, when they’re not grounded in these justice-based values and when they’re not informed by, you know, people who are doing anti-oppression work. So those are some of the narratives that we contend with.

NI: What brought you into the Changemaker Authors cohort? What vision for narrative justice is your work trying to cultivate?

Hans: I love this question. My book, Future Husband, is about my own personal experiences, which I think is a great place to start conversations, because people don’t care about data. They care about stories. And, you know, data can support that. But so at first glance, the tagline for this book that I’ve been working with is about coming of age when puberty never happens, which is my own story, and it’s for young adults, maybe older teens. What I’m looking at exploring is medicine’s role in enforcing colonial gender ideals on intersex people, particularly how white femininity is kind of built and put on people. I experienced growing up in the absence of certain bodily milestones, and contended with messages that I had, that everyone, not just parents, have received on white womanhood. How do you train someone to be a white woman in this world, when so much of that is connected to bodily milestones? So, I’m interested in telling a story that isn’t just about intersex representation on a shallow level; I want to grapple with this enforcement of white womanhood. And it’s very much about queerness, too. I think, for queer people, learning how to be in the world and learning the language of care takes a while, especially when you’re contending with these additional, you know, marginalized identities. This particular story happens at the “lavender relationship” stage. I’d always find myself thinking that there was something wrong with me because I had to figure out how to be with men. And, you know, early on that was always gay boys. You know, in high school, I think everyone was confused, terribly confused, but there was a sweetness and a kindness to it, right? Because there was an attraction to this queerness, but no one knew what to do with all of these kinds of frameworks that get pushed onto people – white femininity, white masculinity –that are enforced and taught, especially in the suburban, homogeneous environment that I grew up in. And so I’m really interested in how people learn queerness and how people build like those relational and self awareness skills. Why does it seem easier for assumed male people to realize like I’m a gay boy, as opposed to someone who’s been raised to be a white woman? There’s this assumption that being in a relationship and providing for a man is about suffering and self-sacrifice in that context, or at least that’s maybe something that I internalized. And so it, it felt like it took a lot longer to kind of come to some of these ideas. What does it mean to grow up and become a white woman? There’s this sentiment that’s says, I’m wrong. I’m the problem. I need to work so hard to make myself smaller in order to continue the status quo. So, that’s something that I really want to have conversations about that, with the lens of intersex issues.

NI: What inspired to produce a graphic novel for young adults? What drew you to that particular genre?

Hans: I love comics. I grew up with comics, like manga and shoujo. Unlike maybe most of American media, these genres showed me the power of femininity and queerness, not necessarily just in terms of relationships or attraction, but in terms of, models of care and friendship. Those themes were so huge and so formative. If you think of Sailor Moon, there are characters that we would describe as queer characters, just in terms of gender presentation. And the narratives [in Japanese comic genres] aren’t just flat romantic narratives. They go beyond just one romantic partnership. So I want to bring the inherently queer aspects of friendship into this book, how we prioritize different types of love and care. Maybe that doesn’t look like a traditional, one-on-one, heterosexual marriage? Because that’s a pretty new and weird institution. But comics really showed me a lot of narrative possibility models, a lot of relationship possibility models. I’m just so in love with the format, especially for this particular story and especially for young adults.

My book is about a character who’s a teenager who’s trying to find her way, who’s has dreams of being an artist, being a creative, and finding autonomy and expression. But the character is dealing with the fact that at sixteen, you know, her body isn’t looking or changing in the way other people think that it should. That puts her into this place where other people are policing and watching her. Like, why isn’t this happening? Why aren’t we having these bodily milestones? That creates a lot of cycles of self doubt, right? For me and for a lot of people who are either raised assume female or even people who come to that later through being trans or other avenues, there’s all this baggage about femininity. It somehow needs to be situated in relationship to male attention. I’m trying to find solace in this relationship with, you know, a closeted gay boy who’s also confused and trying to figure out a lot of stuff. They’re both just slamming into walls. How do you navigate and deal with all of those expectations and come out with a vision for what you want, your own autonomy, your own life, your own relational style? I don’t know if it’s accurate to truly call it a romance in the sense of genre, especially if the assumption with romance is that they ride off into the sunset. It’s not that narrative, but it expands on what that can mean and look like in a queer sense.

NI: We published a piece earlier this summer called “Gender is a story we tell ourselves” by Dominique Dickie, who does game game design and engages with science fiction. They talked a lot about worldbuilding and how the graphic novels that they were reading exposed them to trans identities and trans masculinity in subtle ways.

Hans: One of my mentors in this project is Maia Kobabe, the cartoonist who wrote Genderqueer, which, I want to say, is one of the books most heavily targeted by book bans. The title, you know, has the word “queer” in it, which makes it an easier target. And it does depict people grappling with sexuality, gender issues, transgender identity, which – goodness forbid – children know exist. So, it’s been a really hot subject of contention, to the point that conservative lawmakers have brought “obscenity” lawsuits against it. It just shows the power of that possibility model and what lengths people will go to to advance an anti-bodily autonomy agenda because they recognize that power.

NI: I want to go back to something you said earlier in this interview. You said intersex people have a lot of wisdom to offer. Can you tell us more about that? What do you wish people understood about intersex identities?

Hans: I mean, it’s so beautiful, right? I was just having this conversation with somebody yesterday. I deeply wish that people could see that we don’t have to organize society based on very narrow bodily definitions of reproductive roles. What if there was another way? What if it was great for everyone? The artist Alok talks about this so beautifully. What they say is, sometimes, people feel threatened by queer people, trans people, intersex people, because we inherently represent possibility models. We represent different ways of being in the world. Some people find that very frightening or very challenging. But for those who are able to receive those models, there’s so much wisdom and there’s so much beauty to be gained.