Librada Gonzalez's search for queer Cuban history sparks an archival project

Field Notes is where writers show us the creativity, perspectives, and strategies of everyday organizers who are pushing us toward a world where a truly just, multiracial democracy is possible. In this Field Note, Eileen Sosin Martínez shows us how a community archivist is bringing queer Cuban history to the public.

Contributor

Eileen Sosin Martínez

Date,

21 May, 2024

“What I had found in the libraries was not even a fraction of what it was in the street, in the people’s houses… That was like a revelation: that those things had to be searched out there, and that much, much of it has remained unfound”.

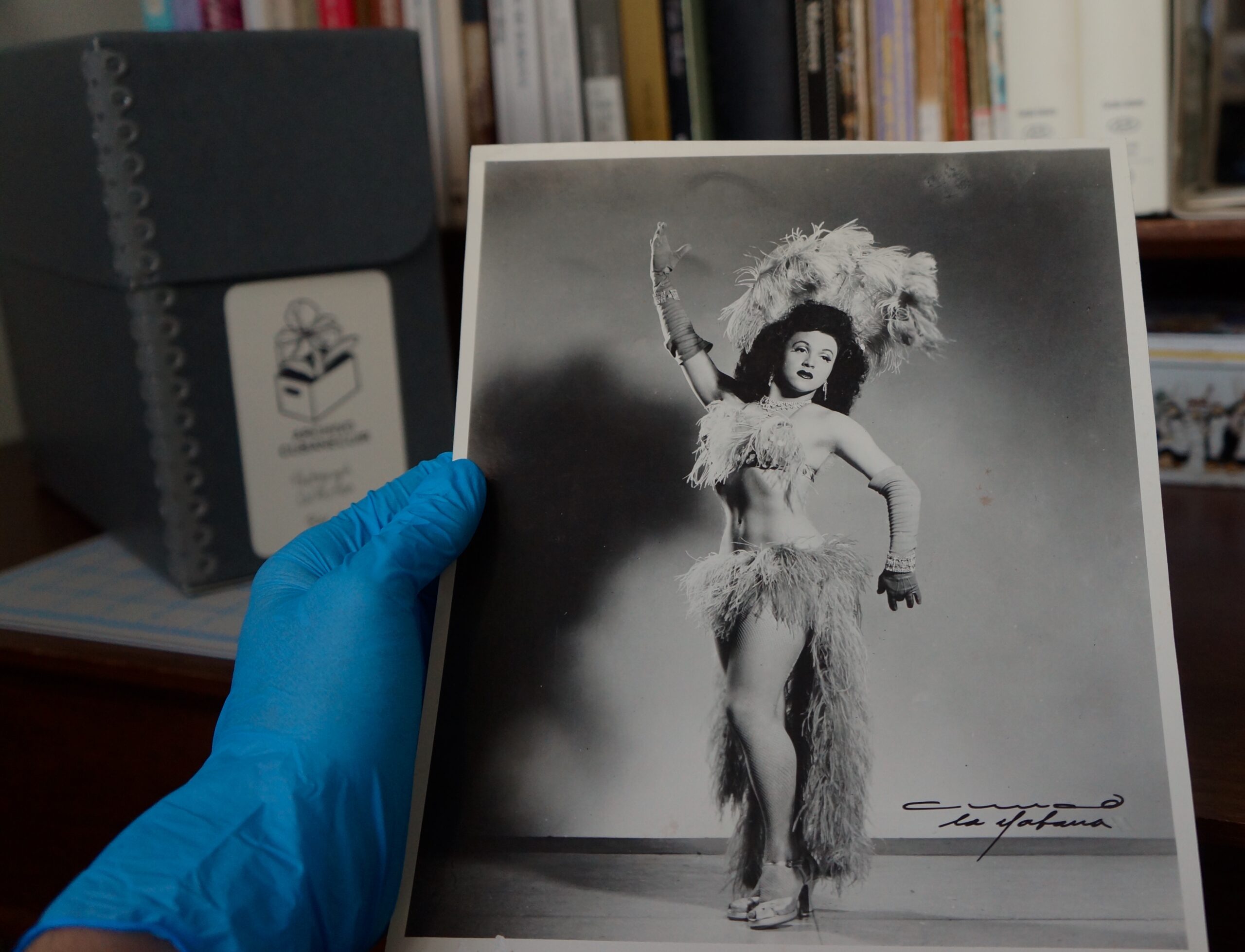

After almost four years, New York-based trans activist and researcher Librada González Fernández has gathered more than 600 pieces – ranging from photos and vinyl records to letters, videotapes and diaries- which inform the Archivo Cubanecuir (Cuban Queer Archive), a project that aims to rebuild the history of people who challenged gender norms.

Librada noticed that official records spoke to the trauma, suffering and the criminalization of LGBTIQ+ people in Cuba. “That was not queer history, but the history of transphobia and homophobia”.

She started the archive because, until the 90s and early 2000s, representations of trans people were largely distorted, fictions created by cisgender people that had nothing to do with reality of trans life.

“It made me very sad that trans women, specifically, [have] one of the most visible identities in the queer community, and at the same time, we are the ones who have been given the least amount of space to talk about our lives, to define ourselves, to say what does matter…”.

For me to understand that my trans identity was actually both cultural and gendered… that changed my life. Because not only I am a trans woman: I am a Cuban trans woman"

It was crucial for trans people to create their own narrative. Along the way, Librada came to the conclusion that preservation was as important as analyzing those documents under the light of dignity and context. “I have the custody, and also the interpretative power”.

Now she’s building the online repository where all the pieces will be visible and searchable. Since she lacks formal education as an archivist, Librada has counted on the help of Arien González Crespo, a Cuban academic librarian working in El Colegio de México, who has given her technical assistance.

Arien taught her that she could tell a story through archival data, and that aligns with one of her goals. She wished for more than a website with scanned images and descriptions, but a platform where users could make connections between documents.

Coincidentally, both González come from Placetas, a small city in Villa Clara, at the center of Cuba. Long ago, Arien envisioned that a project like this would exist. She attended an online presentation about the archive, and felt that it was about her, that she was one of those individuals. So she decided to contact Librada in order to collaborate.

According to Arien, some of the core values of Archivo Cubanecuir are to disseminate the LGBTIQ+ heritage and to exert the right to memory. “It is important that individuals from Cuban LGBTIQ+ communities can see themselves as subjects with a past and, therefore, with a future to build in which they can and should be fundamental agents”, she stressed.

For instance, the Archivo de la Memoria Trans, from Argentina –an archive that first inspired Librada- was crucial for the approval of the 2012 Gender Identity Law. Cuban activists have also been pushing for a similar law to be passed in the island nation.

Recently, the Cuban Heritage Collection from the University of Miami donated some magazines to the project. Indeed, the archive encompasses memories from Cuba and the exile. Information is both in Spanish and English, so it can reach natives and second- or third-generation Cuban descendants mainly settled in the United States that barely have a connection with Cuban history.

“For me to understand that my trans identity was actually both cultural and gendered… that changed my life. Because not only I am a trans woman: I am a Cuban trans woman," Librada highlighted.

She is not expecting Archivo Cubanecuir to have an immediate, broad-reaching impact, but hopes it can, bit by bit, as people discover it. In the meantime, the Cuban queer community has responded positively. “I think that people acknowledged that there was a necessity. From the start, their support has been unconditional”.

While dreaming of having a physical space in Cuba to exhibit the pieces in the future, Librada hopes the archive motivates people to create their own research and collections.

Eileen Sosin Martínez is a Cuban freelance journalist covering economy, gender issues, the environment and culture. They've contributed to Open Democracy, the International Journalist’s Network, and Climate Tracker. Eileen is a member of the Oxford Climate Journalism Network of the Reuters Institute and a co-curator of Share Magazine.