How Oral Histories Bring Justice to Families Separated at the Border

In Field Notes, writers show us the creativity, perspectives, and strategies of everyday organizers who are pushing us toward a world where a truly just, multiracial democracy is possible. Between 2017 - 2018, the Trump administration separated 5,000 children from their families at the U.S. border without process records on how to reunite them— the so-called “Zero Tolerance Policy.” Today, the Biden administration is still trying to reunite 1,000 children with their families. Last month, a settlement was reached in a class-action lawsuit between the families against the Federal government that would allow them to live and work in the U.S. and apply for asylum. In this Field Note, Fanny Julissa García shows us how oral history practices were used to successfully advocate on behalf of family members.

Contributor

Fanny Julissa García

Date,

08 November, 2023

Señor Daniel speaks in a low and cautious tone. He is on a cell phone in front of his home. He has just arrived from working under the unrelenting hot sun to clear a field for cattle grazing. His take home pay for this work is about fifty quetzales. The equivalent of six dollars.

He tells me this is not enough to feed his wife and two children and that he used to have three children under his care, but the U.S. government took his teenage son in 2017 when he tried to migrate into the country.

“We are going to separate you from your son because you are a criminal,” a border official told him shortly before they placed Señor Daniel and his son in adjacent cells with walls made of glass. Father and son could see each other, but they could not comfort each other during what would prove to be one of the most terrifying experiences of their lives.

Over the phone line, I could hear his throat clenching as he struggled to explain what happened to him without breaking down. “We could always see each other. My son looked sad but at least I could see him. Then they took him, and I didn’t see him again. I spent 27 days in detention, and I never saw my son again.”

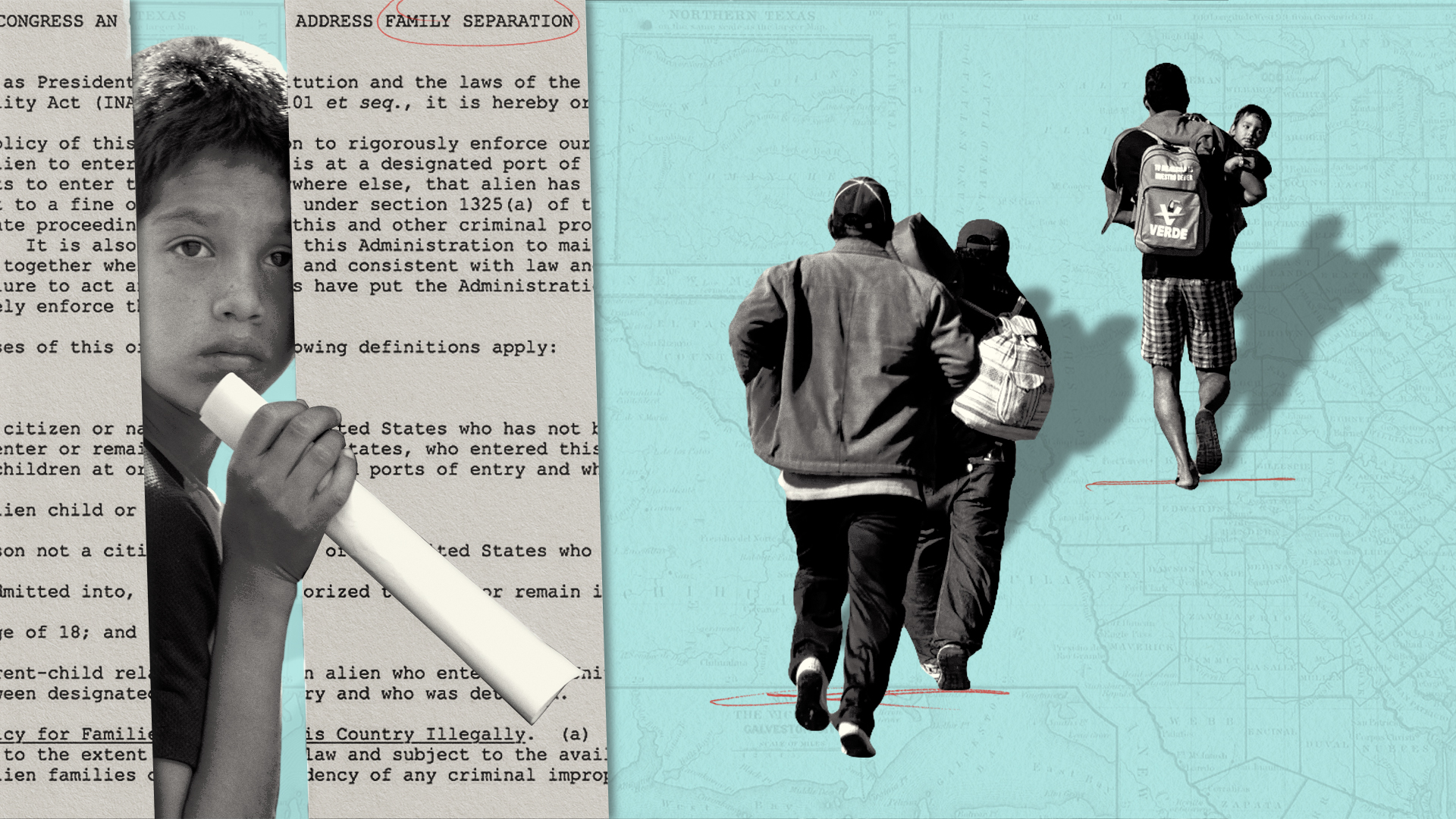

This conversation with Señor Daniel is one of more than thirty conducted with Central American migrant families as part of Separated: Stories of Injustice and Solidarity. This oral history project documents the Trump administration’s infamous Zero Tolerance policy of 2017 and 2018, in which border authorities forcibly separated unprecedented numbers of migrant parents and children arriving at the US-Mexico border.

The interviews began during the first year of the pandemic in 2020 and occurred via telephone after the parents were returned back to their home countries without their children. The conversations with parents and children who were separated are long, deep, complex, and emotionally wrenching. And yet, everyone interviewed expressed an urgent desire for their story to be heard and recorded. The families do not want to be seen as tragic figures, and so they use the only thing at their disposal to fight against injustice - their story.

The oral histories with separated families document a historic human rights violation that has become a reference point for immigration policy and border enforcement. The families recognize themselves as protagonists of this history and believe the reckoning and the prevention of any future policies like the one that harmed them must begin with their experiences.

The narrators shared their story because they want it to serve a purpose - they want family separation to never happen again to any family. This is the mandate almost all the parents repeated during our conversations. As one mother we interviewed stated, “I would be willing to tell my story a thousand times over because I don’t want this to happen again, especially with my people, people from other countries. We are human beings.”

In response to this call to action, the oral histories in the collection have been used to advocate for a public apology, restitution, and permanent status for the families that were separated.

For example: in 2021, a meeting was organized with Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas by various immigration justice organizations to meet with parents impacted by Zero Tolerance. Many of them had already been reunited with their children under different legal processes.

However, parents who had been deported back to their home countries and were living in rural communities in Guatemala were not going to be able to attend the meeting due to irregular access to WiFi in their villages and limited or no experience with video conferencing platforms like Zoom. Yet, these families were perhaps more in need of being heard during this meeting because after several years, they had still not been reunited with their sons and daughters.

In lieu of their presence at the meeting, audio excerpts were created from the oral history interviews and shared along with a photo and short bio of the parents and their child and submitted to the meeting organizers. The parents advocated for permanent status and reunification not just for themselves but also for other parents who were impacted by Zero Tolerance. According to the meeting organizers, this was the first time in history that a sitting Homeland Security secretary met with migrants seeking refuge in the United States.

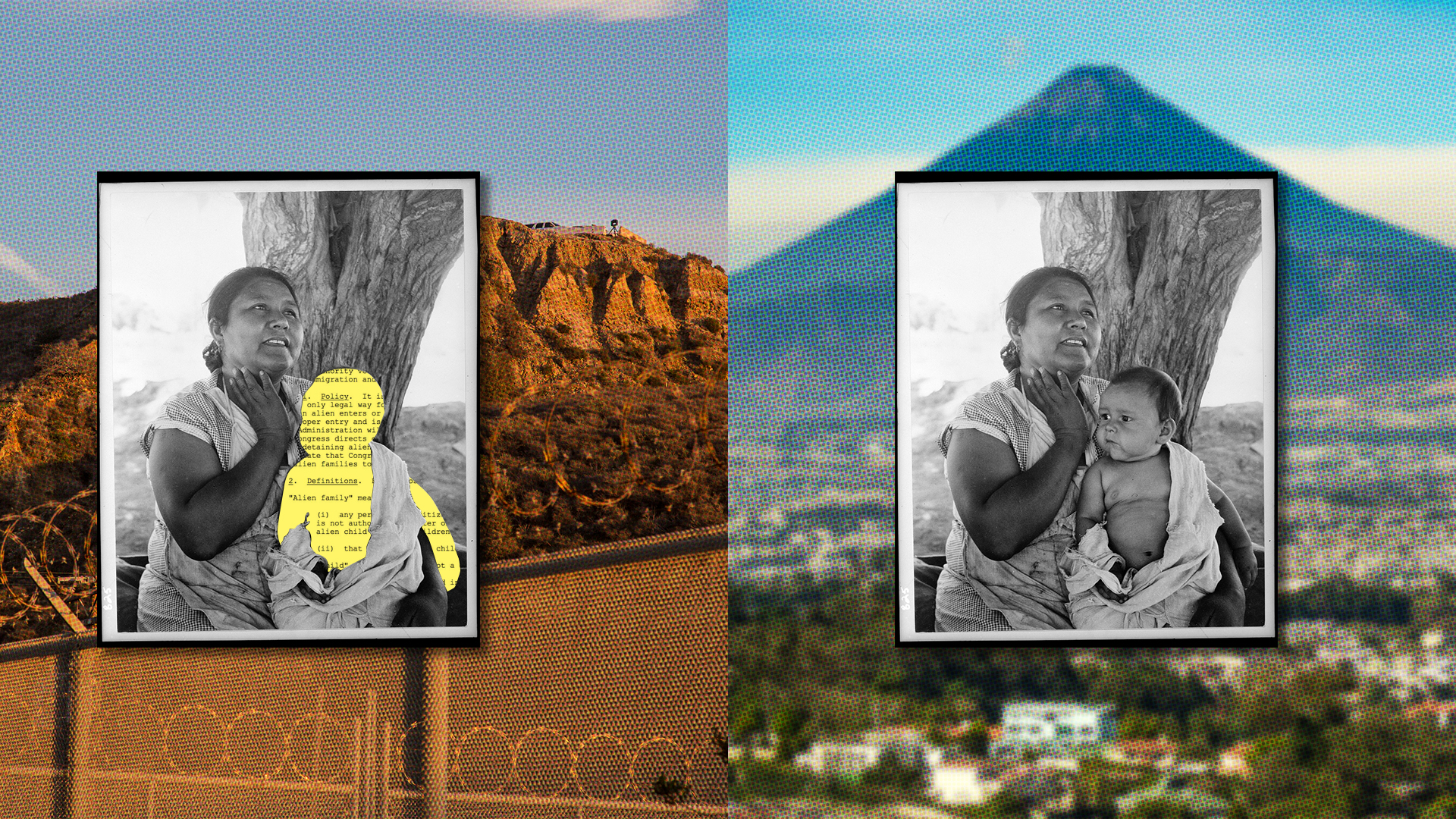

In August of the same year, we published an opinion piece in The Washington Post advocating for financial restitution and permanent legal status for parents and children who were separated under Zero Tolerance. The op-ed featured the story of an Indigenous mother and her son who were reunified but are still facing a precarious situation due to temporary status and economic challenges. The oral histories of both mother and son form part of the collection of stories included in the Separated project.

The following year in January 2022, the Department of Homeland Security put out a call for public comment for recommendations on how to “minimize the separation of migrant parents and legal guardians entering the United States.” The comments would be used in the drafting of a report required by the White House’s Interagency Task Force on the Reunification of Families.

Due to our ongoing relationships with the families who contributed their stories to the oral history project, we were able to reach out to them and assist in preparing their comments for submission. Eight families contributed to this endeavor thereby creating a clear example of their burgeoning contributions to American civic society and history. In Spanish, one father wrote in his statement, “Por favor no separen a familias. La separación de familias es un delito contra los niños, los padres, y la humanidad.” Please do not separate families. Family separation is a crime against children, parents, and humanity.

Additionally, stories from Separated informed a policy brief by the Women's Refugee Commission. The brief details the impact of the separation, surveys the urgent needs of reunified families for various services, and recommends policies needed to prevent a future administration from separating families. The brief draws on quotes from the interviews to illustrate the long-lasting impact of the separation.

Our initial contact with separated families was facilitated by the Women’s Refugee Commission and Justice in Motion, two immigration justice organizations supporting migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. From there, we went on to develop a relationship with the families. We committed to investing time, heart, and resources into the partnerships established with the project’s narrators.

Every time a public deliverable like the Op Ed was presented to us, we reached out to families and requested their consent. We never moved forward without their approval, and not just a yes would suffice. We also queried them about how they wanted to be represented, and they told us. For example, the mom featured in the Op Ed wanted us to make sure to mention her Indigeneity. “My identity is always erased,” she said. “So, make sure you mention it.” And we did.

The media covered family separation extensively but they only focused on the tragedy of separation, the arbitrary nature of the injustice, and the policy implications. The coverage showed children in cages and distraught parents, but not their anger and determination to reunite.

In contrast, the long oral histories provide a space for the parents and children to explore various parts of their existence including core values, identity, joy, hardship, and tenacity. The interviews are full of memories of the trauma of separation but there is also anger at a government that saw them as criminals and traffickers, rather than as people who have a human right to do whatever possible to make life better for themselves and their children.

Oral history is a field capable of creating an exchange that holds all of these experiences, and facilitates opportunities for narrators to see themselves as protagonists of their lives, and as such, capable of turning an experience that has happened to them into narrative power to advocate for change.

The parents and children who contributed their story to Separated understand the importance of narrative power intimately, because when the entire world has moved on from one crisis to the next, all they have is the memory of what happened to them. Under the Biden Administration, many parents have been reunified with their children in the United States, but without permanent legal status, they live with anxiety about the potential of another separation.

The families separated under the Trump Administration’s Zero Tolerance policy cannot and will not forget, and they use their story to ensure the public remembers.

Fanny Julissa Garcia is an oral historian and narrative change strategist. She serves as the Project & Communications Director for Separated: Stories of Injustice and Solidarity. The project began in 2019 in partnership with History professor Nara Milanich, and received initial funding from the Oral History Association and the Mellon Foundation through a grant administered by Barnard College. In 2020, we partnered with the Women’s Refugee Commission and in 2022, the project received additional support from the National Endowment for the Humanities and Justice in Motion. To learn more about the project, visit separatedoralhistories.org