How a Durham-based crisis response arm is reimagining public safety

Field Notes is where writers show us the creativity, perspectives, and strategies of everyday organizers who are pushing us toward a world where a truly just, multiracial democracy is possible. In this Field Note, Yewande Addie shows us an alternative crisis model in Durham, North Carolina, is changing how communities approach mental health and public safety.

Contributor

Yewande Addie

Date,

21 May, 2024

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and a historic summer of unrest, leaders across the U.S. faced mounting pressure to defund police in response to communities' understandable fear of systemic violence. This watershed moment was underscored by the declaration of racism as a threat to public health, formally establishing the link between public safety and health equity.

Stories about the history of policing in the U.S. and its roots in slave patrols dominated headlines. Other stories circulated about other unarmed killings, the blue wall of silence and the limitations of relying on police to manage crises. These stories fueled interest in a change, leading Durham, North Carolina to commission RTI International, a nonprofit research institute, to research better alternatives to responding to 911 calls.

RTI analyzed three years of 911 call data and explored alternative crisis response models. Of nearly 900,000 responses, only 1.3% of calls were related to violent crime. Police were often dispatched to manage real or perceived mental health emergencies, but lacked both training and tools to fully support people’s needs. Conditions remained untreated, leading to more frequent 9-1-1 calls. It was impossible to ignore that this crisis response model needed help.

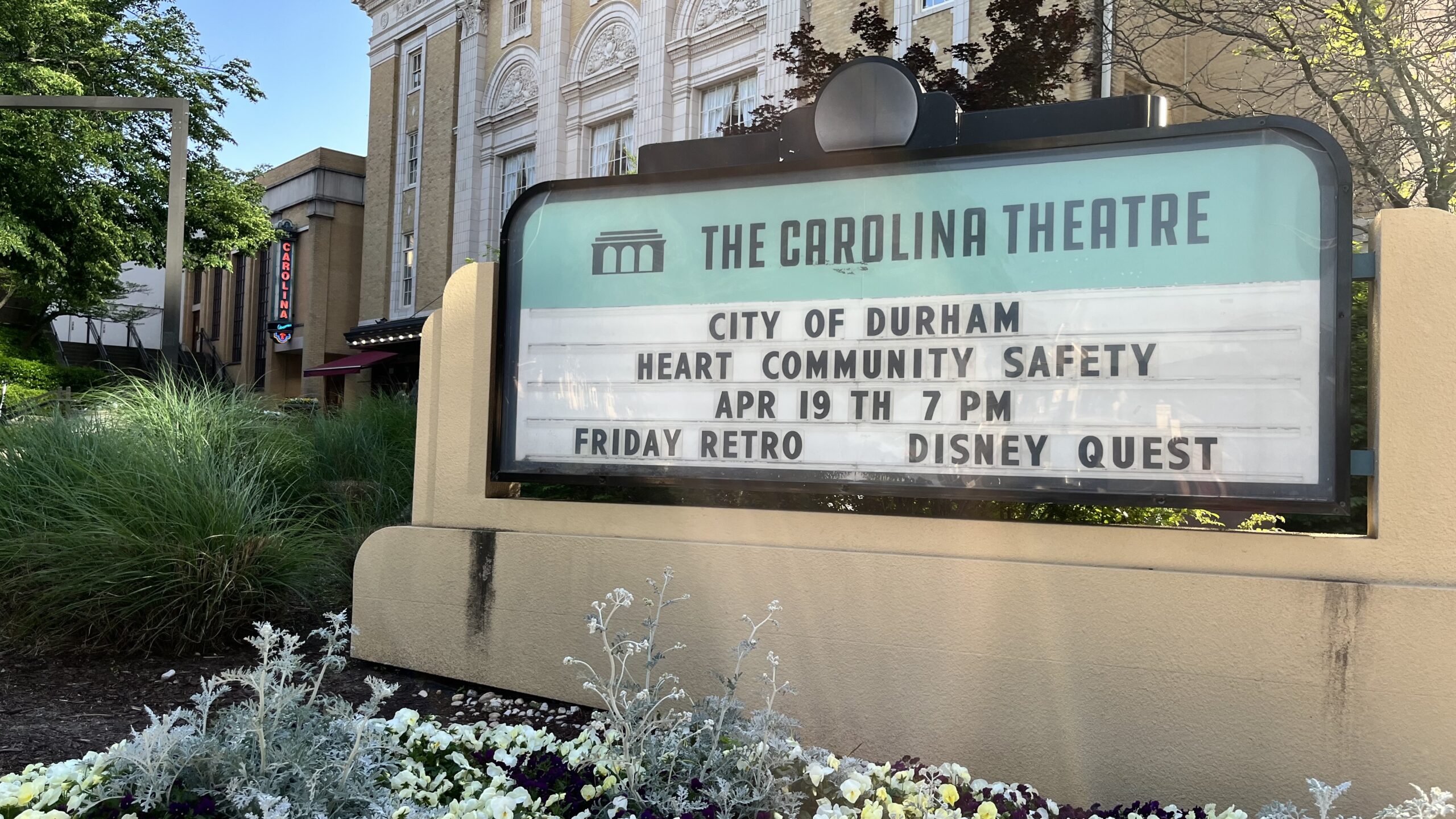

Recognizing the need for a different approach to calls for nonviolent assistance, the city of Durham piloted the Durham Community Safety Department (DCSD), an alternative crisis response program. The Holistic Empathetic Assistance Response Team, known locally as HEART, became the city's first public safety unit staffed with mental health clinicians, peer support specialists, and EMTs.

Understanding the potential for other cities to learn from these pilots, RTI International’s Transformative Research Unit for Equity (TRUE) created a documentary that explores the process, tensions and deep collaboration needed between police officers and mental health clinicians in HEART’s first 6 months of operation. DCSD's Director, Ryan Smith, said during the group's orientation phase, staff members continued to mention how they had a "real heart" for the work, inspiring the organization's name and intention to root their work in love and care.

They just need to feel a sense of safety, a sense of validation, a sense of love. We kind of shy away from that word love, especially in a professional setting, but it's what we do."

“It's easy to be a clinician– it's easy to think about and conceptualize and theorize in a framework…but a lot of times people don't need a clinician, they just need connection” said Kirby Jones, a HEART staff member featured in the documentary. “They just need to feel a sense of safety, a sense of validation, a sense of love. We kind of shy away from that word love, especially in a professional setting, but it's what we do.”

In addition to responding to high and low risk quality of life calls with police, members of the HEART team fill a unique social welfare gap by connecting community members in need with compassionate care. The impact of this outreach was revealed in testimonials in the film.

One community member recalled the deep emotional response he had to HEART staff intervening when he, his partner and newborn were experiencing unexpected housing insecurity:

“They gave us shelter and they gave us Pampers. We needed Pampers…I didn't want to ask for it, but they actually showed that they care and they kept calling us and checking on us and they made me feel like all of it that I had built up in me from so much pressure… I actually started crying, man, because I was so in pain. I was holding it for so long, I couldn't hold it no more.”

And that’s the nature of what alternative crisis response programs are designed to do–offer some sense of care and dignity in crisis. In fact, “one of the earliest first response alternative programs in the country, [Pittsburgh’s Freedom House Enterprise Ambulance Service] was established in the 1960s” to do just that. In response to Black community members in Pittsburgh feeling ‘indignity and fear when forced to rely on police officers for transportation to the hospital,’ residents created an alternative program that was staffed by trained Black community members to provide emergency medical services.

The HEART program is an extension of that foundation. But as noble as alternative crisis models are, they require a shift in culture that isn’t always welcome. In telling this story, Dilsey Davis, a director and producer on the film, said there were two major barrier beliefs she wanted the project to help shift.

“When people think about alternative crisis models, they think about the safety risks around sending unarmed people into the community,” Davis said. “There’s also this belief that groups like these somehow threaten police by taking away their jobs or that they should be seen as adversarial.”

But Davis said she believes sometimes people just need to see examples of change to know what’s possible. Her intention with this film was for it to be a visual case study. “My hope was that this documentary would make more people across the United States aware of this initiative and encourage them to push for programs like this,” Dilsey said. “I also wanted it to influence police and other city staff to show that we can have both the police and new programs.”

Anise Vance, Assistant Director of DCSD, says the latter point about cities having both systems independent of each other can also be a complicated goal because unlike HEART, similar programs end up couched within existing response arms, eventually languishing.

“Sticking an alternative response program inside of a public health agency, or a police department, or a 9-1-1 center or fire department, is going to mean that alternative response program is never able to grow to its fullest, and is never able to thrive, and it ends up not fulfilling its promise as a diversionary response that can truly meet *neighbor’s needs,” Vance said.

Since the film’s debut last year, the HEART program has become wildly popular, with widespread requests for expanded services and other cities expressing interest in replicating the alternative crisis care model.

Vance said DCSD has directly supported about 35 cities aiming to create similar programs. Despite the looming challenges around structure and scale that remain for some cities, he said the documentary and their department’s growth both serve as sources of inspiration to Durham and a host of other cities, just like Dilsey wanted.

The documentary film has been celebrated by *neighbors near and far since its debut last spring.. It’s also been circulated at film festivals, community-hosted screenings with city leadership, by researchers at behavioral specialist conferences, and in university courses.

“This is what we wanted. We were trying to reach community members, policy makers (local and state), researchers, police, and city or county leaders, including non-profit leaders,” Davis said. “And I think we have been more than successful–I can only hope we reach even more people.”

Currently, Dilsey and her team are still doing narrative measurement research to see the full scope of the film’s impact on audiences, but the success of the HEART program and positive reception to its origin story are a testament to what can be done when care is the main ingredient in community interventions and storymaking.

*The term "neighbor" in the context of this blog and within HEART is a term of endearment used to reference community members and signal a sense of connection and closeness to people under their jurisdiction of care.

Yewande O. Addie is a narrative change researcher in RTI’s Transformative Research Unity for Equity (TRUE).