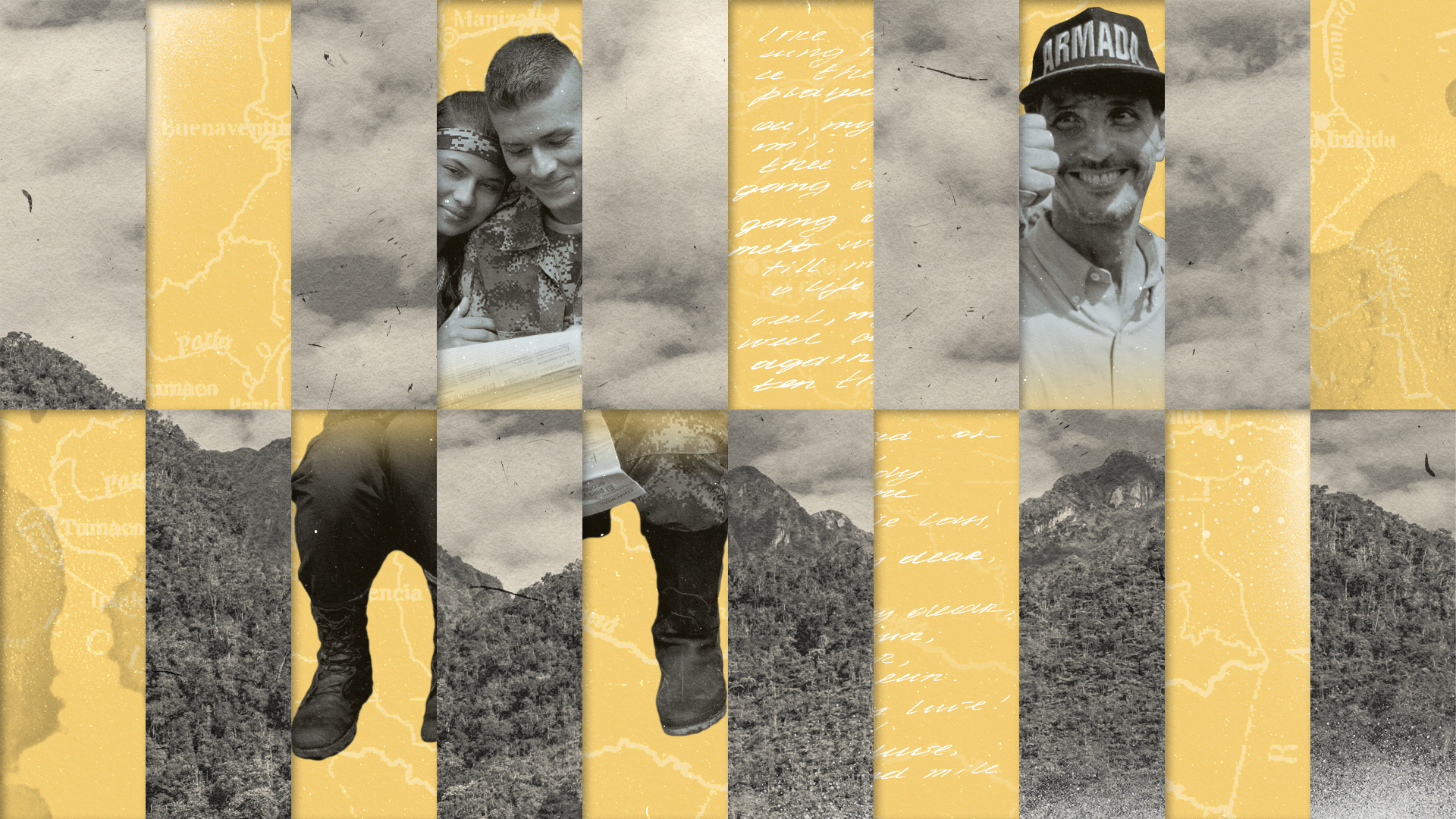

Fernando Araujo’s Journey From Captivity to Compassion

In Field Notes, writers show us the creativity, perspectives, and strategies of everyday organizers who are pushing us toward a world where a truly just, multiracial democracy is possible. In this Field Note, Martina Castellanos reflects on the internal journey of a man held captive for six years.

Contributor

Martina Castellanos

Date,

21 May, 2024

When Fernando Araujo awoke on his wife's birthday, their first as a married couple, he had every reason to believe the day would be like any other. Araujo’s time as Minister of Development under Colombia’s Conservative President Andres Pastrana was behind him and he was about to embark on a new consulting venture. On December 4, 2000, at the dawn of a new century that slid Colombia even further into socio-economic crisis, Araujo’s naiveté came to an abrupt end.

At noon, Araujo received a call from Ruby, his former spouse and the mother of their four children, expressing concerns about their safety saying “I worry about this country and for the future of our family.” Araujo reassured her that nothing would harm them, alluding to how President Pastrana’s peace process would bring harmony to the country. And with that exchange, he set off on his daily run.

In the early 2000s, Colombia supplied as much as 90 percent of the world’s cocaine, and the production and trafficking of illicit narcotics provided the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) with much of its revenue. Its secondary source of income is derived from kidnappings and extortion. The FARC, a Marxist-Leninist guerilla group, was founded in the 1960s after a decade of systematic political violence known as La Violencia where an estimated 200,000 people were killed. While there’s no single explanation for why violence erupted, its roots can be traced back to colonialism, an economic crisis in agriculture, corruption, a weak educational system, extreme partisanship, and poverty.

All those economic, political, and social factors came crashing down on Araujo that sultry December day. “And then, they got me,” he explained. Two assailants pounced on Araujo, one from the front and the other from behind a neighboring wall; they had him pinned to a van's trunk in moments. As they drove out of the city, Araujo lay in the car with a handgun to his temple, and a submachine gun directed at his chest. Miles away from the confines of the van, negotiations for peace between President Pastrana and the FARC hit a roadblock as the FARC announced the suspension of talks indefinitely.

Araujo lay awake that night, his mind inundated with questions: “Where am I? What do they want? What will they do to me? What will happen to my wife? How are my kids?” He was placed under around-the-clock watch, any escape attempt on his behalf would result in immediate execution; failure to carry out this command would mean death for the vigilant guards themselves. The instructions of killing Araujo on the spot if needed, effectively severed all lines of communication or even the want of one between himself and the guards. The only potential lifeline for Araujo was a wire transfer of 20 million dollars— a sum he did not possess. The mere mention of it, caused him to faint.

Having been raised with a belief in the power of cooperation, he embraced every chance to lend a hand.

Araujo remained quiet the days following his capture, yet he remembers that on December 31, 2000 he initiated a conversation with one of his guards:

“Peter, it's December 31st, a day meant for family,” Araujo said.

“I don't have a family. They were killed by the guerrilla,” Peter responded.

Araujo saw the pain in Peter's eyes, and a realization dawned on him: his presence here was not going to be as easily negotiable, transient, or unscathed as he had first thought. While this understanding settled in, he began to think about the type of relationship he wanted to have with Peter and the rest of the guerilleros.

As we sit in rocking chairs in his apartment, surrounded by numerous history books detailing Colombian history and the elusive peace our country seeks today, Araujo reflects on his thoughts that New Years Day:

“At that moment, my primary goal was to determine the kind of relationships I aimed to cultivate during my time there. I could choose aggression in response to theirs, lashing out with hurtful words, ignoring them, or displaying my anger. Or, I could choose positivity. Maybe I could even change their mind through conversation, though I soon discovered it was near impossible.”

Despite Araujo and the guerrilleros' initial reluctance to speak, months of consistent interaction eventually thawed the cold relationships, particularly with Gabriel. Gabriel, one of Araujo’s guards who had joined the camp in December at the age of 19, had been recruited by the FARC before his eleventh birthday. Initially he boasted about his early involvement and subsequent rise to commander, yet combat had left its mark in the form of shrapnel lodged in his skull. This injury ultimately caused him debilitating migraines, and due to this, he retired from his leadership role and arrived to Araujo’s camp.

During his night shifts, Gabriel would often seek solace in conversation with Araujo, expressing weariness with the cycle of violence and its futility. “Violence breeds more violence,” he would lament. While some guerilleros were receptive to such sentiments, others dismissed Araujo’s perspective completely, labeling him an “oligarch” unfit to understand their reality. Finding that his words failed to resonate with some, Araujo resolved to take action.

In the FARC, the value of collaboration was viewed as weakness, creating an environment where individuals toiled independently without seeking aid. Still, Araujo diverged from this mindset, having been raised with a belief in the power of cooperation. Consequently, he embraced every chance to lend a hand; in a culture where words were considered a plentiful currency, actions were possibly seen as a rare and appreciated commodity. Whether this action came in the form of lightening the guerilleros burdens during long treks, deciphering radio instructions, or even teaching English, Araujo volunteered. He once penned a love letter to Gabriel's girlfriend, eloquently expressing Gabriel's affection and devotion to her.

After six years in captivity, Araujo finally managed to escape on New Year's Day, December 2006. Six years had elapsed since the peace plans halted, and Araujo returned to civilization with President Uribe now in command, adopting a more aggressive stance on the FARC. When asked about this, Fernando remarked, "I do not justify the FARC's acts in any way, but I understand their human condition." Some guerilleros remained, while others departed after Araujo's liberation. Gabriel ultimately left the FARC, underwent the process of reintegrating into Colombian society, and continues to work closely with Araujo to this day.

Martina Castellanos is an MFA student at Columbia University. She is the former Managing Editor-in-Chief of the Economics Review at New York University. Her writing focuses on topics within the South American region.