Thinking with our eyes: Understanding the power of visual narrative

Visual narrative includes the photos and video we see in front of us every day. It’s also the fuzzy scenes stored in our memory. These images shape stories, narratives and even deeply held values. How do we put images to work in our narrative practice? Resource Media’s Liz Banse recently wrote a series of articles about imagery and narrative for the Visual Story Lab. We asked Liz to share a version of those insights here.

In the past several years, foundations and nonprofits have embraced the concept of narratives as crucial to making social change.

Narratives sort the chaotic problems of our world into a range of acceptable understandings and solutions. It’s simply human nature to use deep story frames to put our world into context and to share our contexts with others.

Images have the power to subconsciously trigger or lock in a narrative in a fraction of a second, long before the more rational parts of our brain have a chance to interpret text.

The current pandemic and related economic collapse put the need to create new narratives in bold relief. The social, economic and environmental crises laid bare by COVID-19 lend new urgency to redefining our country’s priorities. As the initial shock of the pandemic wanes, people are beginning to imagine what a more just and equitable post-pandemic society might look like.

But we risk being ineffective if we neglect one key element of redefining and reshaping narratives: the power of imagery.

As we push for a bolder, more inclusive future, we need to understand the full range of reframing tools at our disposal. While social change advocates are getting more adept at articulating narratives as text, we have room to grow in understanding and strategically using the visual element of narratives.

If you are narrative geeks like we are here at Resource Media, you have probably read lengthy essays about the power of narratives to drive policy change. We are big believers in this and have seen it play out over and over again in campaigns. However, little time has been spent on the incredible power of visuals in setting the frame. In fact, we know that images have the power to subconsciously trigger or lock in a narrative in a fraction of a second, long before the more rational parts of our brain have a chance to interpret text.

Cognitive scientists have shown that our brains respond first to visual input, far faster than absorbing text on a page or audio in a real-life setting. Neurologists have documented that images are a direct pathway to the amygdala, which regulates our emotions, and emotions strongly influence decision-making. As we consider how to advance new narratives to create a more humane post-COVID world, we need to develop a visual strategy to connect with the right emotions to inform decision-making.

So, six months since the coronavirus arrived in the United States, what is the dominant narrative on the pandemic? Well, it depends on what media ecosystem you swim in.

Let’s start with the story-based narrative. One message points to data showing that while everyone is vulnerable to the disease, the coronavirus is disproportionately impacting communities of color. The pandemic is daylighting how systemic inequalities and structural racism compound the harm. This narrative puts the collective health of the community over the rights of the individual and emphasizes our shared responsibility to protect the most vulnerable members of our society. The values at play in this narrative are health, family, community and a shared sense of personal responsibility.

Competing messages emphasize a different story – the “economic lockdown” and state orders around social distancing threaten liberty and prosperity. This rallies people around the idea that a public-health centered approach is yet another example of government overreach. This is a narrative decades in the making. Recall Ronald Reagan’s quip that, “government isn’t the solution, government is the problem,” or the mantra “government governs best when it governs least.”

Those are the text-driven narratives. But what is the visual narrative of the pandemic in this moment? Whose side is winning the battle of images?

Often in narratives, the messenger – who is doing the talking – sets the visual narrative and frame for the viewer or listener. By virtue of who we see talking, our brains make subconscious assumptions about the story we’re about to hear. Before the story even starts, in many cases we are already choosing sides.

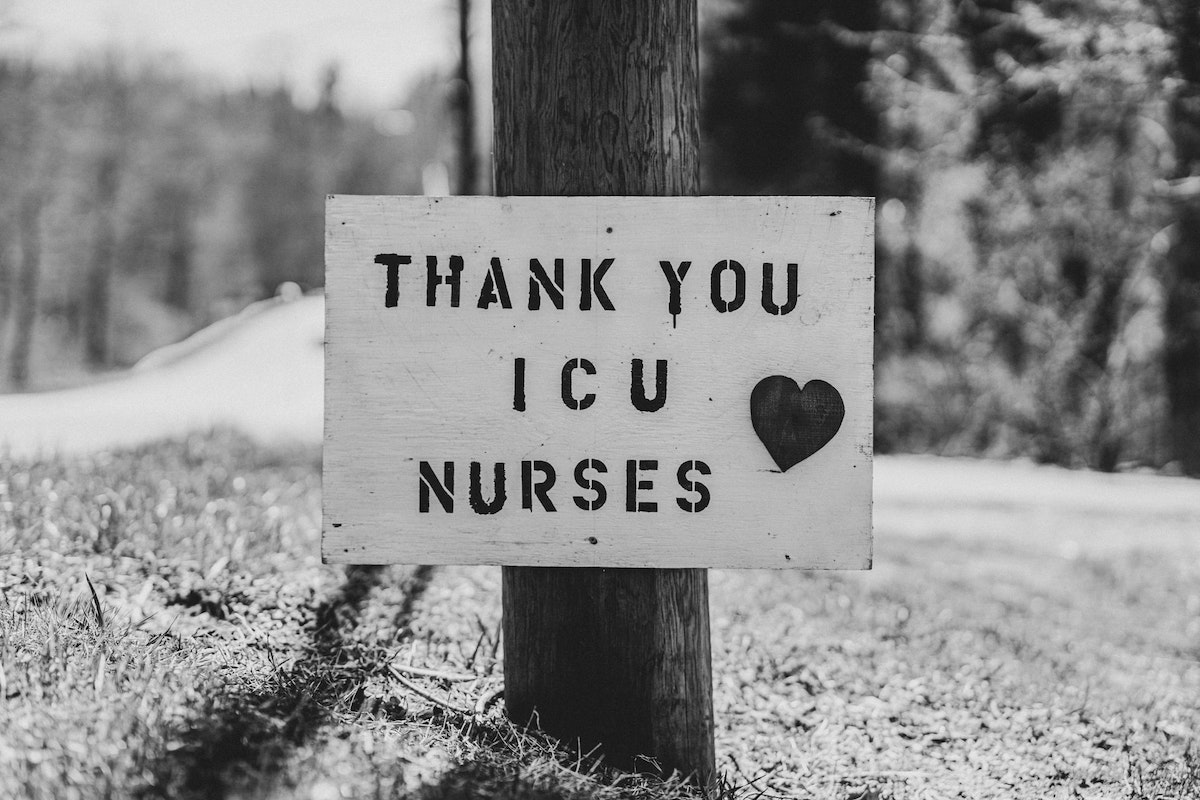

‘Thank you’ sign nailed to a telephone pole, celebrating ICU nurses during the Coronavirus pandemic of 2019/2020. Photo by Nicholas Bartos.

In the early days of the pandemic, with the novelty of stay-at-home orders, social media was rife with images of people finding community even while apart. The messengers were people like us, and the storylines emphasized how we’re all in this together, with the virus as a common threat.

In May, a new set of visuals was pushed into the frame. The media began serving up men in camouflage, armed with guns and flags against a backdrop of state capitol buildings. Their hand-held signs telegraphed angry messages about government’s threat to their freedom and prosperity.

Community-minded interests moved past the “flattening the curve” graph to imagery of nurses in scrubs and other heroes of the frontlines, as well as helping to elevate other essential workers, from grocery store clerks to bus drivers. The victims were elderly grandparents locked behind glass in a nursing home, frightened patients in oxygen masks, or, worse yet, unfortunate souls whose bodies overwhelmed morgues and cemeteries. The villains were those whose selfish behavior put lives at risk.

Solidarity with Essential Workers. Image by Melanie Cervantes.

Don’t forget masks! Masks present a powerful visual of the battle between two deep narratives: community care and individualism. Those who wear masks per the guidance of health authorities consider it a sign of respect and caring for others, especially the most vulnerable. Mask wearing is a community responsibility. Those who shun masks and heap scorn on the mask wearers have pronounced it government imposing its will on others.

Visual Narrative at Work

Each of us can use the power of a frame-setting visual for good in narrative development. For many years, climate advocates used visuals highlighting polar bears and melting glaciers, memorably captured in Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth. Collectively, a narrative was established that put polar bears and receding glaciers at the center. With Gore becoming a polarizing political figure and non-human actors (the polar bears and glaciers) as the protagonists, climate change remained a low public policy priority for almost two decades.

Young people around the globe are rewriting this climate narrative. Today, when the public is asked what comes to their mind when they hear the phrase “climate change” they are responding with something more catalyzing than glaciated landscapes or politicians. Our world’s youth – from Greta Thunberg to Varshini Prakash of the Sunrise Movement are the new face of the climate movement.

From youth and members of frontline communities showing up and protesting outside global climate conferences to the Fridays for Future school strikes, their visual is deeply intertwined with their narrative, including setting up a clear contrast to the (mostly) men in suits deciding our future within the halls of power. As well, instead of melting ice caps, today climate activists young and old point to problems closer to home such as coastal erosion and more frequent storms. These clearly answer the question, “Why should we act on this now?”

Youth demand climate action. Photo by Callum Shaw.

Another example of using imagery to shift narratives is the effort to defeat the Trump Administration’s 2018 proposal to open more than 90% of U.S. coasts to new offshore oil and gas drilling. This battle has served as an opportunity to seed a new narrative on ocean health and expand public and policy maker support for protecting our marine ecosystems.

At the outset, we faced two entrenched dominant narratives: first, that “the ocean is too big to fail” or too vast for people to do lasting harm. A second, that the choice was between protecting jobs vs. protecting the environment.

One powerful way to dislodge an entrenched narrative is to insert new voices into the conversation. With offshore drilling, our coastal coalitions did that by shining the spotlight on coastal businesses who rely on stronger ocean protections for their livelihoods. Owners of seafood restaurants, dive shops and beach hotels allowed us to tell a very different visual story, one that shifted the center of power and influence and effectively changed the narrative around offshore drilling.

Business owners proved authentic, credible messengers to make the case that stronger environmental protections are essential in protecting their livelihoods instead of a threat to them. In this narrative paradigm of jobs and the environment, with ocean stewardship tied to the value of prosperity, policies like offshore drilling were seen in an entirely different light. The images, including the faces and livelihoods of people affected, present the visual narrative. The stories they tell feed into a larger narrative.

Four Questions

As we work to upend hurtful, false narratives and replace them with inspiring new stories that put us on the path to a more just and equitable society, we challenge our social sector colleagues to think through what are the most strategic visuals to match the narratives our community puts forward by asking yourself these four questions:

- What is the current visual story you are advancing, and what emotions is it likely engaging?

- What visuals are your opponents advancing, and what emotions are they likely engaging and to what end?

- What are the emotions you need to engage to connect audiences to the values and decisions you want to advance?

- What visuals—and which messengers—connect to those emotions?

Remember, we think with our eyes. So, when we think of narratives, think about images.